Should some version of the New Prosperity copper-gold mine ever be built in Tsilhqot’in territory, it will only be with the full consent of the Tsilhqot’in First Nation. An agreement signed last month between the B.C. Government, Tsilhqot’in First Nation and Taseko Mines attempts to resolve a long-standing conflict that has prevented mine development in Tsilhqot’in country.

While the agreement is being hailed by the Mining Association of BC (MABC) as an “important milestone in reconciliation…that allows for the future development of this valuable critical mineral resource,” the Association of Mineral Exploration (AME) is raising concerns. The agreement comes with a new land use plan which, when stacked on top of another new land use plan for Northwestern B.C., is giving AME members some angina.

“With the one-year Northwest land use planning processes underway, and now this additional newly announced land use planning process, we ask the government to publicly commit to not releasing any new land use plans,” AME board chairperson Trish Jacques said in a news release.

The agreement, signed in June, aims to resolve a decades-long conflict between the Tsilhqot’in and Taseko Mines over the New Prosperity mine — said to be the largest undeveloped copper-gold deposit in Canada. The mine was first proposed in the 1990s, and the Tsilhqot’in have been fighting it ever since. “This agreement resolves a damaging and value-destructive dispute and acknowledges Taseko’s commercial interests in the New Prosperity property and the cultural significance of the Teztan Area to the Tsilhqot’in Nation,” Taseko Mines president Stuart McDonald said in a press release.

Taseko’s original Prosperity mine project received a provincial environmental certificate in 2010, but it was rejected by the Stephen Harper government after a federal Environmental Assessment Act review. The original mine plan would have required draining a pristine lake — Fish Lake, which the Tsilhqot’in call Teztan Biny — to be used for tailings storage. The Tsilhqot’in’s objections have been fierce, and their legal hand was strengthened in 2014 when the Supreme Court of Canada recognized Tsilhqot’in title to a portion of their traditional territory.

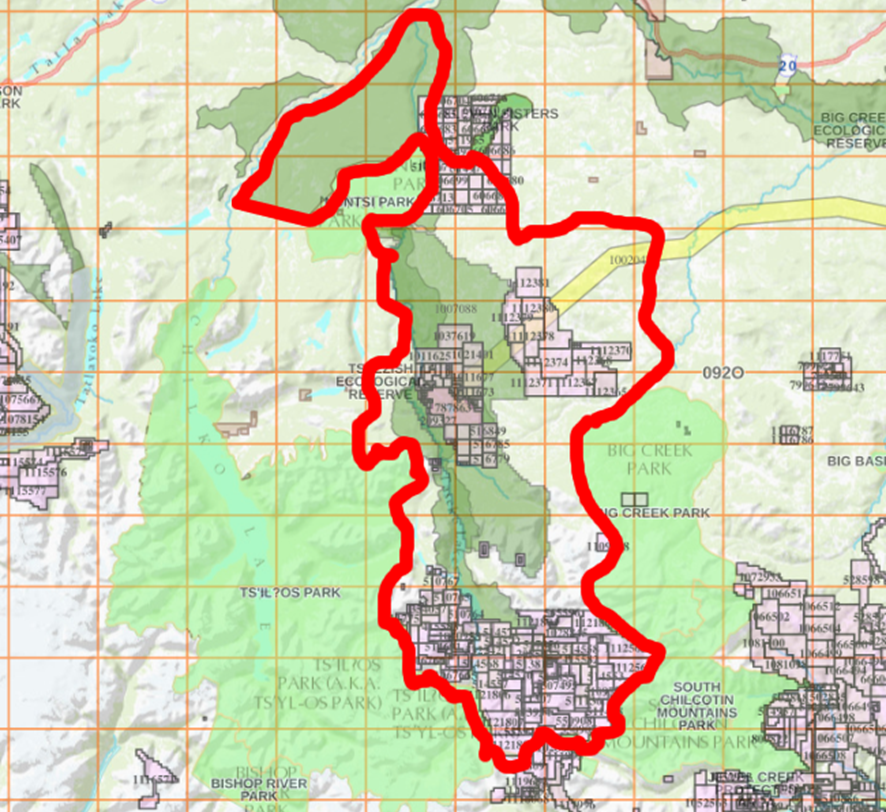

Fish Lake lies outside Tsilhqot’in title lands, but the Supreme Court affirmed the Tsilhqot’in have “proven Aboriginal rights” to hunt, fish and trap in the area, as well as use the area for ceremonial purposes. After Prosperity was rejected, Taseko came back with a revised plan — New Prosperity — that would avoid draining Fish Lake, with a tailings pond positioned two kilometers upstream. That too was rejected by the federal government, and over the years Taseko and the Tsilhqot’in have launched numerous court challenges. The agreement signed in June terminates all litigation over the project. Two consent agreements have been signed — one with the province, the other with Taseko — that gives the Tsilhqot’in control over what does or doesn’t happen within their traditional territory. As part of the agreement, a new land use plan will be developed for the tribal park that the Tsilhqot’in declared in 2014 — Dasiqox Nexwagwez’an.

The agreement provides an exit strategy for Taseko while preserving value. The company will get $75 million from the B.C. government, and will retain 77.5% of its mineral tenures. The Tsilhqot’in will be given 22.5% equity in the New Prosperity mineral tenures. But if the New Prosperity mine, or some version of it, is ever built, it will have to be built and operated by some other company. “Taseko has committed to not be the proponent (operator) of future mineral exploration and development activity at New Prosperity Project, and can divest some or all of its interest at any time, including to other mining companies,” a government news release states.

The B.C. government plans, through an order in council, to apply a Section 7 provision for the Tsilhqot’in, similar to the one applied for the Tahltan First Nation. This will require the consent of the Tsilhqot’in for all reviewable projects — i.e. projects requiring a B.C. environmental assessment. Before any mine proposal is considered, a new land use plan needs to be completed. “The first thing is a land use plan for the area,” Chief Roger William told me. “Anything that’s in the area has to be Tsilhqot’in-led. “This agreement means Teztan Biny is protected from any mining, any drilling, any exploration without the consent of the Tsilhqot’in people.”

The land use plan encompasses the Dasiqox Nexwagwezʔan tribal park that the Tsilhqot’in declared in 2014. The B.C. government says it will “invite broad public and stakeholder participation” in developing the plan. There are 12 companies with mineral claims in the area to be subject to the new land use plan, according to the AME. They worry about what new consent powers will mean for mineral exploration in the area.

“For the mineral exploration sector to be successful, investment in mineral exploration projects is required,” Jacques said. “It is unreasonable for the government to expect investment in the mineral exploration sector without ensuring certainty of land access, which is the foundational requirement to support the search for the critical minerals societies need.”

Nelson Bennett’s column appears weekly at Resource Works News. Contact him at nelson@resourceworks.com