Projects in the national interest should spark big ideas. But in British Columbia, the discussion feels narrowly confined.

Today’s focus is limited to individual projects, with little sign of a broader, fifty-year vision. Yet that’s precisely what’s at stake: building infrastructure over the next 10 to 15 years that will remain in use for decades to come.

We’re talking about a generational project, one that must confront three stubborn, generational problems:

- Urban centres, overwhelmed, with no clear path to catching up.

- Goods-producing jobs, too few.

- Education, too many people working in jobs they’re overqualified for.

Fortunately, British Columbia has past generational visions that can shine a light on the road ahead.

This account from BC’s Knowledge Network highlights the profound impact of the province-wide utility development surge in the 1950s, led by Premier W.A.C. Bennett:

“When he became premier in 1952, much of B.C. remained largely cut off from the rest of the province, untouched by modern infrastructure.”

Key initiatives of the era included completing BC Rail to Prince George and establishing both BC Ferries and BC Hydro.

At the same time, fishing, mining, logging, and private hydroelectric projects laid the foundation for a manufacturing corridor stretching along Highway 16, from Prince Rupert to Prince George, anchored by processing plants, pulp and paper mills, sawmills, and an aluminum smelter. Tens of thousands of new residents followed, building up the surrounding communities.

EXPO 86 symbolized and ushered in a new, forward-looking vision for British Columbia. Vancouver was transformed into the world-class city we know today. The event sparked major infrastructure initiatives: SkyTrain, Science World, Plaza of Nations, B.C. Place, and Canada Place Trade and Convention Centre.

It also led to the Coquihalla Highway, linking the Okanagan to Vancouver more efficiently. That connection helped draw tech companies, universities, and medical centres to the region. By 2021, three of Canada’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas were located along this corridor.

As shown by the experiences of the 1950s and late 1980s into the 1990s, utilities are facilitators of towns and cities, not the builders. You need things to do or goods to make that create opportunities to attract people in numbers.

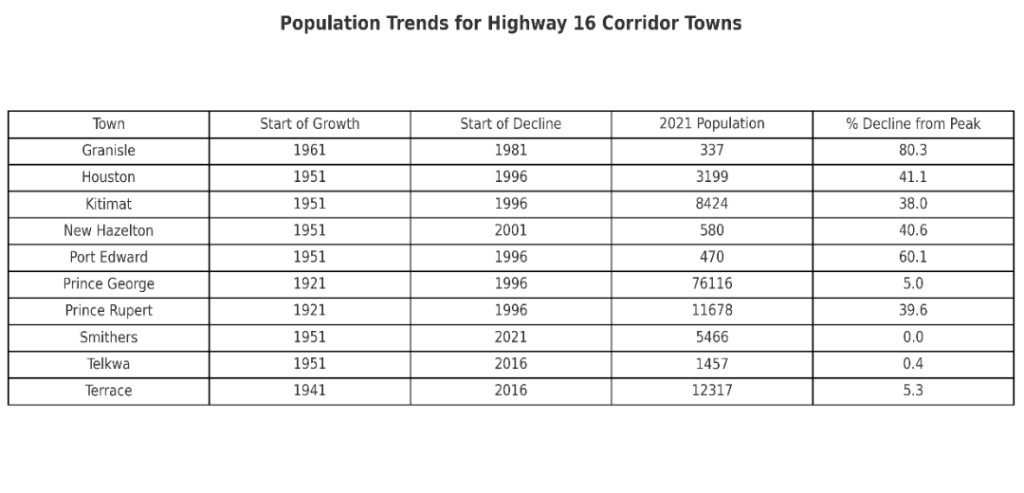

As the chart below shows, when opportunities decline, communities wilt.

Chart Notes:

- Prince Rupert and Prince George were already established industrial and service hubs by 1921.

- Most other communities experienced their primary growth during the 1950s, driven by intensive industrial investment.

- The population decline beginning in the 1990s reflects multiple factors: changing attitudes toward resource extraction, consolidation and amalgamation of legacy industries, global competition, softwood lumber tariffs and export taxes, and a clear policy shift favouring services over industrial development.

The population decline beginning in the 1990s reflects multiple factors: changing attitudes toward resource extraction, consolidation and amalgamation of legacy industries, global competition, softwood lumber tariffs and export taxes, and a clear policy shift favouring services over industrial development. Statistics Canada, Prepared by BC Stats 2023

Urban centres are overwhelmed, with no clear path to catching up

Canada’s current obsession with dense urban centres has failed to meet housing expectations or contain the cost of living, particularly for working people. To alleviate the pressure, we need to draw people away from urban centres by offering them opportunities.

Goods-producing jobs are too few

“Contrary to the claims of successive Canadian federal governments of both Conservative and Liberal stripes that free trade agreements promote the creation of middle-class jobs for Canadians, the empirical evidence suggests the opposite has been the case. The quality of new jobs has fallen steadily over the last two decades and virtually all new jobs created in the economy have been in the lower-paying service sector. While global trade liberalization can hardly be the culprit behind the lack of real wage growth in services, since the sector is the most insulated from direct low-wage-import competition from abroad, trade liberalization’s devastating impact on job creation in the goods-producing industry has forced an ever-increasing share of the labour force to be employed by the much lower-paying service sector,” wrote Jeff Rubin in 2018 for the Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Resource and manufacturing jobs raise labour productivity and generate a wage premium for working people. That premium widens the pathway to a middle-class life, encourages family formation, and strengthens communities of all sizes.

Too many people are working in jobs they’re overqualified for.

Politicians and educational institutions often claim, with pride, that Canadians have the “highest level of education in 2021, above all other G7 countries,” reported Statistics Canada.

According to the think-tank Cardus, which defines today’s working class as ‘those in jobs that do not require a post-secondary credential’, what they don’t take ownership of is: “The proportion of [workers] that is over-credentialed has grown steadily over the last two decades, from 42 percent in 2006 to 56 percent in 2024. The proportion with a university degree has explicitly more than doubled, from 9 percent in 2006 to 19 percent in 2024.”

Resource and manufacturing jobs create more opportunities for workers without formal credentials, but they also generate demand for highly credentialed professionals like specialists, managers, and engineers. These jobs often carry a wage premium and help drive productivity across the entire economy.

What should the narrative include when we speak of pipelines, electrical grids, and marine terminals?

To serve the greater good of the province, those of us who support and discuss resource development should emphasize that we are laying the foundation of a fifty-year vision.

Over that time, hundreds of thousands of people have relocated, and will continue to relocate, along the corridor. Investments in the North will generate government revenue, ease housing demand in the South, and lower the per capita cost of delivering public services in the North.

We must encourage mineral refining and smelting in Northern BC. We need to raise awareness of the benefits of manufacturing, assembly, warehousing, and packaging at or near the Port of Prince Rupert.

Critical to attracting out-of-region manufacturers is straightforward, secure access to timber, ensuring a vibrant and confident local industry.

The vision must be a comprehensive trade and logistics corridor. Otherwise, it’s just products moving from one place to another. When local value is being added, public resistance to controversial elements is lessened to a degree.

Of course, the key is good-faith relationships between First Nations, proponents, community members, workers, and stakeholders, those committed to balancing prosperity with environmental care.

The Windsor–Toronto–Montreal corridor isn’t a manufacturing powerhouse because of Highway 401. It’s because of what was built along it: foundries, assembly plants, storage, packaging, and logistics, spread across hundreds of villages, towns, and cities.

That’s what makes a corridor a living organism.

Jim Rushton is a 46-year veteran of BC’s resource and transportation sectors, with experience in union representation, economic development, and terminal management.

Photo credit to the Province of British Columbia