Last week, gillnet fishermen were allowed to do something they haven’t been able to do for about seven years now – fish for Fraser River sockeye. Even sport fishermen – usually the last in line when it comes to Fraser River sockeye – got an opening. Following several years of decline, with last year’s returns being the lowest on record, Fraser River sockeye have made a stunning comeback. An estimated 9 to 10 million sockeye are now expected to return to the Fraser River – three times the pre-season forecast of 2.9 million.

Based on the abundance of fish that are still flooding back to the Fraser River, commercial gillnet fishermen should, by rights, be allowed to go fishing again this week, though that seems unlikely to happen. “There’s really no reason why it doesn’t open today or tomorrow,” said Ryan McEachern, a gillnet fisherman. But it appears fisheries managers have gotten so used to managing for scarcity that they have forgotten how to manage for abundance. Despite the abundant return, Area E gillnetters were limited to only a couple of days of fishing last week, and a quota of just 235 fish per licence. An overly cautious approach to fisheries management has resulted in lost opportunities, as well as the resignation of a long-serving member of the Pacific Salmon Commission, who quit in frustration.

On August 21, Michael Griswold, a 40-year member of the PSC’s Fraser panel, resigned over what he believes is an “unnecessarily restrictive” management of Fraser River sockeye. “I could no longer support the Canadian government’s position on managing Fraser River sockeye,” Griswold wrote in a resignation letter, which was publicly posted on the BC Salmon Gillnetters Association Facebook page. “It is my firm belief that the Canadian management plan was unnecessarily restrictive on this year’s production of sockeye, which is now assessed at more than four times greater than the pre-season forecast.””There’s huge frustration,” said Greg Taylor, an adviser for Watershed Watch.

Fisheries managers with PSC and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans appear to have been caught flat-footed by an unexpected bounty. The pre-season forecast was for 2.9 million sockeye. But the returns have come in at three times that number – at least 9 million – which the PSC itself noted “is the largest run size observed since 1997, excluding dominant 2022 cycle years.”

Top Photo: Tayah Takasaki, whose family are Area E gillnetters, prepares a Fraser River sockeye for sale off the boat in Steveston. | Nelson Bennett photo

The biggest returns of Fraser River sockeye typically happen in an even year, once every four years – called a dominant year. This year is a sub-dominant year, so returns were not expected to be as large as they have turned out to be. But returns have been so dismal for the past several years that fisheries managers appear to have gotten used to using highly restrictive management practices to protect weaker runs from bycatch. “They never thought about what could happen, or how they had to manage fisheries differently, in this kind of scenario,” Taylor said. “Now they’re trapped in these constraints, which are not biologically supported anymore.”

Area D and E covers the southern coast, from the top of Vancouver Island to the U.S. border. Area D gillnetters got one 41-hour derby style opening, McEachern said, while Area E got two days, but with individual transferable quotas (ITQs) of 235 fish per licence. It was the first time the Area E gillnet fishery was on a quota system.

In total, gillnetters were allowed to catch about 47,000 fish under the quota system, McEachern said. Commercial fishermen have been waiting for a run like this for seven years, so they are disappointed that fishing opportunities were so restrictive. “There was a small fishery in 2019 for a few hours, but it’s fair to say that the last normal commercial fishery was 2018,” McEachern said. “So it’s been seven years.” He said there is now hope that next year – a dominant year run – could be even better than this year’s return.

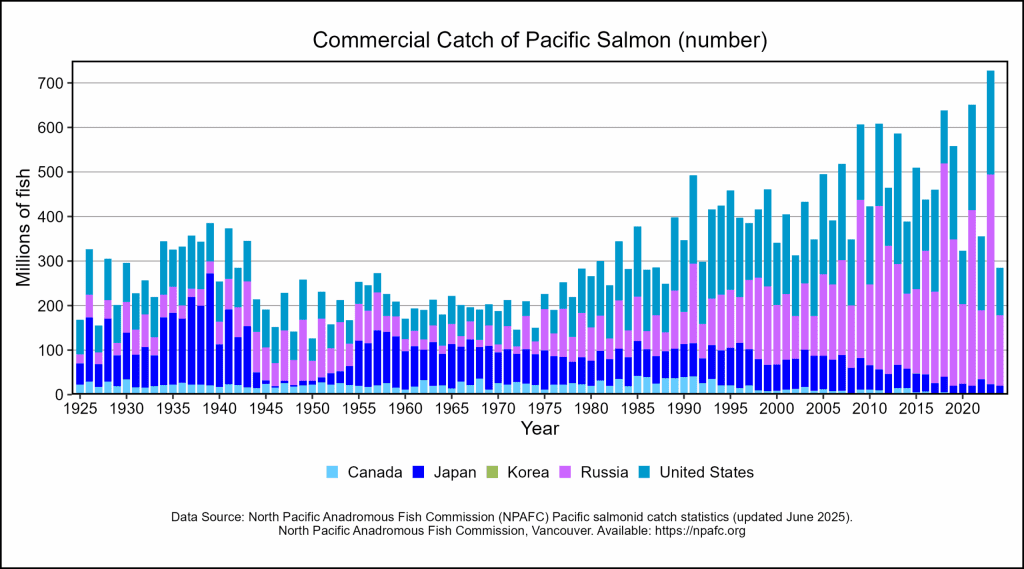

Fraser River sockeye have generally been in decline for about decade, so this year’s abundant return is a welcome signal that stocks may be rebounding. Those opposed to salmon farming have suggested this year’s bounty may be, at least in part, linked to the closure of some open-net salmon farms, which started around 2021.

John Smith, chief of the Tlowitsis Nation, called this link “nonsense” in a recent opinion piece in the Victoria Times–Colonist. “These large sockeye returns have happened during peak biomass salmon farming in B.C., like 2010, and will continue to occur into the future in areas with or without salmon farms because their numbers have nothing to do with fish farms,” he wrote.

‘The Salish Sea is alive right now’

As for sockeye returns elsewhere the Pacific Ocean, Taylor notes that Bristol Bay sockeye returns in Alaska are gigantic, as usual, but weaker than expected in Southeast Alaska. Returns for other systems like the Nass and Skeena rivers have been “OK.”

“The biggest story, in terms of fish so far this year, is Fraser sockeye, and coho and chinooks in the Salish Sea, which is off the charts large,” Taylor said. He points to observations made by renowned fisheries scientist Dick Beamish that the Strait of Georgia appears to be recovering, after a long decline in productivity that started in the 1990s. “That we’re seeing such an abundance of coho, chinook, sockeye, humpback whales, the Salish Sea is alive right now,” Taylor said.

In recent years, the federal government through the Pacific Salmon Strategy has invested in salmon habitat protection and restoration, and imposed restrictions on the commercial and sport fishing sectors – efforts which may now be paying dividends. “There’s no question that’s helpful,” Beamish told me. “But there’s also no question that the ultimate regulation of all salmon species is the capacity of the ocean to support their survival.” He notes that the Strait of Georgia has become more productive, in terms of food production for fish.

“The best chinook salmon return to the Fraser River in history was 2023,” he noted. He also notes that, in recent years, there has been some cooling in the Gulf of Alaska, following a series of heat waves that started around a decade ago. “So you could have a combination of very good food production in the Strait of Georgia, along with cooling in the Gulf of Alaska,” Beamish said. “All of that could have contributed to much better ocean survival than was expected in the models. “It’s possible the Strait of Georgia is producing more food now for the sockeye. The test of that idea will be next year, when we get an Adams year.”

Nelson Bennett’s column appears weekly at Resource Works News. Contact him at nelson@resourceworks.com.