Petronas’ recent announcement that it wants to back several more Canadian LNG projects should be a wake-up call for Ottawa and Victoria.

The Malaysian state energy giant already has about 50 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in Canada, operates the North Montney Joint Venture in northeastern British Columbia, and is a major equity partner in LNG Canada, the $40 billion project in Kitimat that shipped its first cargo to Asia this summer.

Petronas executive vice-president Mohd Jukris Abdul Wahab says the company sees Canada as one of its “major LNG supply bases going forward,” but made clear government support will be key to unlocking the next wave of projects.

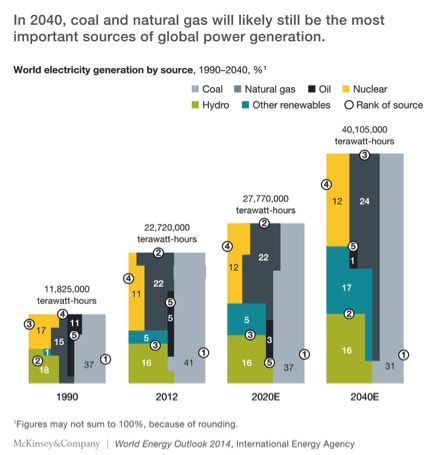

That is not unique to Petronas. The world’s demand for secure, low-emission natural gas is only growing, and B.C. is uniquely positioned to meet it. Japan, one of the biggest LNG importers on the planet, is phasing out coal and actively looking for long-term supply deals. Canadian LNG’s shorter shipping distance from Kitimat to Tokyo, compared to the U.S. Gulf Coast, is a major selling point.

B.C. also has some of the most sustainable LNG facilities in the world, from Indigenous-led Cedar LNG to the planned Ksi Lisims LNG and Woodfibre LNG projects. Cedar LNG, majority-owned by the Haisla Nation, will run on B.C. Hydro’s renewable power, making it one of the lowest-emitting LNG plants globally.

Further down the coast at Squamish, Woodfibre LNG will be the first LNG export facility in Canada to include electric-drive compressors for liquefaction, powered by renewable hydroelectricity. This innovation will avoid approximately 230,470 tonnes of CO₂ equivalent per year versus gas-fired liquefaction. That is equivalent to the emissions from over 70,000 gasoline-powered passenger vehicles driven for one year.

Using the E-Drive for liquefaction eliminates the single largest source of GHG emissions found in typical LNG facilities and is the cornerstone of the company’s Net-Zero strategy.

This is not just about exports. As the National Bank of Canada recently pointed out, natural gas is the lifeblood of Canadian manufacturing, supplying 34 percent of the sector’s energy needs and keeping costs competitive with the U.S. and other G7 countries.

More than half of Eastern Canada’s gas is imported from the U.S., leaving Ontario and Quebec exposed to foreign supply risks. Expanding domestic gas infrastructure could secure Central Canada’s industry, cut costs, and enhance national resilience, while supporting LNG exports from the West Coast.

B.C. has the resources to deliver. The province’s known natural gas reserves are enough to supply domestic consumption for at least 160 years at 2013 levels, and that is without counting future discoveries. In fact, reserves have grown over time thanks to exploration and technology. Critics who say LNG exports will leave B.C. short-changed ignore the sheer scale of these deposits.

The opportunity is huge, but will not wait forever. U.S. President Donald Trump has revived plans for a $44 billion Alaska LNG project aimed at the same Asian markets B.C. hopes to serve. His administration is already lobbying Japan to sign long-term deals, and Alaska’s proximity, combined with Washington’s aggressive regulatory fast-tracking, poses a serious competitive threat.

Canada’s window is open now, but history shows how quickly it can slam shut.

The missed chance to export LNG to Europe in the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, a market the U.S. now dominates, should be a cautionary tale. The U.S. is projected to export 150 million tonnes of LNG annually by 2029, eleven times Canada’s expected capacity. If we do not accelerate, we risk being locked out of Asia by faster-moving American rivals.

Some of B.C.’s political leaders understand this. Premier David Eby, once an LNG sceptic, now says B.C. will “win the race” to Asian markets and has worked with unlikely allies in the B.C. Conservatives to back LNG as a strategic economic and environmental priority.

They recognize LNG exports can cut global emissions by displacing coal in Asia while delivering billions in investment, thousands of jobs, and unprecedented Indigenous economic participation. There is potential for help on the domestic electricity front as well.

As former Haisla chief councillor Ellis Ross bluntly put it, “Electric drives need huge amounts of electricity that B.C. doesn’t have. Natural gas is dependable but not within CleanBC targets. What will it be?”

The federal government talks about making Canada an “energy superpower” while major investors like TC Energy shift focus to the U.S., where “risk-adjusted returns are meaningfully higher.” Underinvestment is glaring: major resource project investment has dropped from $711 billion in 2015 to $572 billion in 2023.

Public opinion, however, is overwhelmingly supportive, with 91 percent of Canadians backing increased oil and gas exports according to Nanos. B.C. is already an energy bridge for Alberta’s oil via the Trans Mountain Expansion, but LNG is what will truly make it Canada’s gateway to global markets.

The province’s coast could soon host at least three major LNG hubs, all with significant First Nations ownership, a milestone in economic reconciliation. For communities hit hard by decades of forestry and fishing decline, these projects are a lifeline.

The message from Petronas and others is clear: the world wants more Canadian LNG, and B.C. is ready to deliver. But to turn potential into reality, Ottawa and Victoria must align policy with opportunity, simplify approvals, support infrastructure, and secure long-term export deals.

If they do, B.C. will not just be an energy powerhouse alongside Alberta, it will be a cornerstone of global energy security for decades to come. If they do not, Alaska and the U.S. Gulf Coast will be more than happy to take our place.